It almost seems that history has taken a break in the Aachen country at this point. In any case, for a few centuries we do not learn anything more about the fate of the settlements that emerged from the Roman army camps. As the curtain opens to the next act, the scenery has changed. The Franks have firmly established themselves and built an empire that encompasses almost all of mainland Western Europe. Of course, like all empire foundations, this process has not gone off without complications. The initially ruling Merovingians was replaced by the Carolingians. There was heavy infighting within the empire, at times even several kings in the divided empire, until finally, as almost always in history, the strongest, the bravest and smartest prevailed. In this case, he was called Charles The Great (Charlemagne, Karl der Große)

In his time, Aachen was one of the royal court estates where the ruler resided from time to time. A capital as center of an empire was not known at those times. Aachen, once a spa of the Roman legions, had become the court estate, the royal fold, which included numerous royal adjoining courts in the area.

One of those courts, the Salhof on the Wurm, was called "Wormsalt," which means nothing more and nothing less than Salhof on the worm. And Salhof means a manor house, which in its exterior was not significantly different from the other farms, apart from the fact that manor houses and storage facilities were usually slightly larger and firmer buildings.

Wormsalt is the first term recorded on 17 October 870 for today's city of Würselen. The evolution of the name from Wormsalt to Würselen Many other documents can be traced closely through the centuries.

1200: Wormsaldia

1239: Worselden

1300: Wursalda

1350: Wursulden

1372: Wörselden

1558: Wursulen

1616: Wurseln

1616: Würselen

Of course, Würselen is not the only place firstly mentioned by name in the Carolingian period. Numerous settlement centers are built during this period or are called for the first time in documents. They are royal domains, single courtyards, monasteries and defensive buildings. Many of them have become core cells of today's villages and towns. In addition to Würselen, Laurensberg, Bardenberg, Afden, Merkstein, Kirchrath and Vaals were mentioned as early as the 9th century.

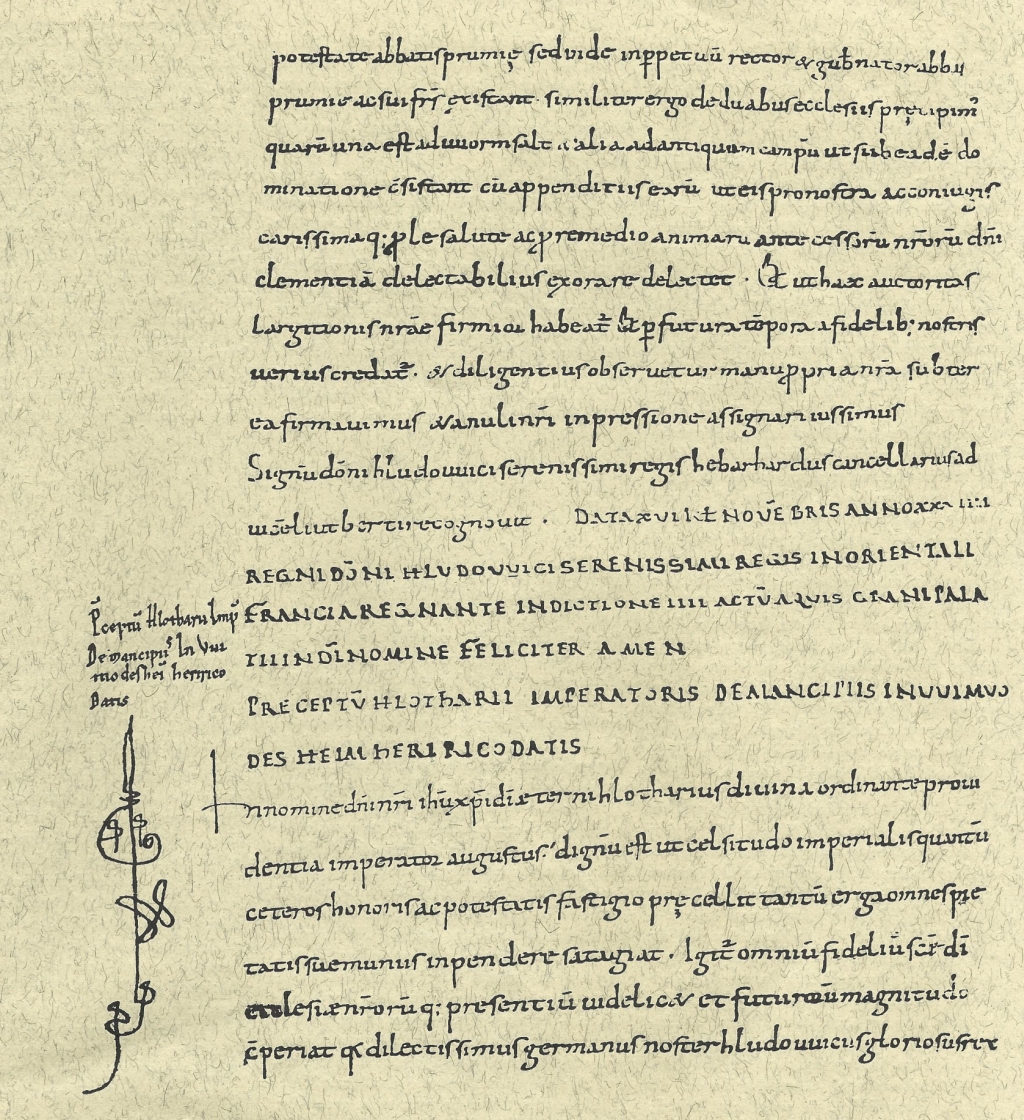

With this document of 17 October 870, Ludwig der Deutsche transferred

the parish church of Würselen to the abbot Ansbold of Prüm.

In it, for the first time, the name Würselen is mentioned in its form at that time:

Wormsalt – the fifth word in the third line.

Like all other farms, the buildings of the Wormsalt and the courtyard church belonging to were made from wood because Würselen, like any places around it, was built on forest soil. And the forests were one of the most important sources of life, which not only provided construction material and fuel, but also valuable fodder for the cattle pole, berries, beechnuts and acorns etc.

The Würselen Salhof was, as one can safely assume, close to the first Würselener church, which was to serve as a court church. It is believed that their place was located roughly on the site of St. Sebastian's parish church today. Why was there a church here in the royal side yard, so early on?

Charlemagne had to make his secondary courtyards independent from any clerical point of view, if the well-thought-out regulations of his country estate order were not to become ineffective on important points. In the 54th chapter of these detailed ordinances, which are intended for the administrators of the individual royal goods, it is stated that the landlords should not be allowed to shirk the work by messing around in other places, whether at fairs or under the Cover fulfillment of ecclesiastical obligations. Thus, if the emperor wanted to prevent his court people from staying away from work - more often in order to carry out real or alleged religious duties in Aachen, he had to give them the opportunity to fulfil these duties on the farm itself. This was the reason for the early foundation of two court churches outside Aachen, one in Würselen, the other in Laurensberg, also a royal tribcourt.

By the way, the river Wurm proved to be a church boundary line for the first time: The courtyards on the right worm side called "over Worm" and at that time also Würselen belonged to the diocese of Cologne, which on the left side belonged to the diocese of Liège.

This was a certain ecclesiastical independence for the secondary estates on one hand. On the other hand, they were in a strong economic dependence on the Aachen Palatinate as the main courtyard. On the adjoining farms, forges, bakers, carpenters, cobblers and, of course, farmers were working. Most likely, the grain was processed by the fields of the Würselener Hof at an early time in the valley of the river Wurm by a royal mill. The wolf mill (Wolfsmühle) in the Wurm-valley is known to have existed long before the year 1200. The supervisory and administration on the Wormsalt was - as with all court estates - the responsibility of a "Meier." In this official designation, the Latin word "maior," meaning the greater one, has been the godfather. All other farm sads were more or less unfree, the landlord commanded directly through the person of the subjects. As late as the 11th century, the entire lowly civil servant, peasant and craftsmanship and butt of the royal courts and their ancillary courtyards were serfs.

This changed, at least for the inhabitants of the Aachen Palatinate, in 1166. Emperor Friedrich Barbarossa from the house of the Hohenstaufen, which in the meantime represented the German rulers, awarded Aachen the city rights: market, wall, toll (customs rights) and an own coin. And all people born in Aachen got their personal freedom. The crown's ownership of the Palatinate had probably melted away greatly through donations from the emperors and kings to faithful followers, to monasteries and pens over the years. On the other hand, the residential area around the Palatinate had been enlarged by merchants and traders who settled there to such an extent that the granting of the city rights was the logical consequence of this development. At the coronation ceremonies and glamorous imperial days that took place in Aachen, the smaller the main courtyard in Aachen, had to rely more and more on the contributions of the secondary courtyards with respect to the provision of accommodation for the princely guests and their entourage.

In any case, little had changed in the conditions on the adjoining stabs compared to Aachen. They still appear to have been under direct royal administration in the 13th century as royal estates. This is indicated by an event from 1214, when the now self-confident citizens of the city of Aachen refused the king admission to their city. Friederich II repents and turns where with his many entourage? To the Königshof Wormsalt, where, unlike Aachen, he remains welcome and finds accommodation.

In one respect, however, a lot has happened in the adjoining houses around Aachen over the centuries: They have grown larger over time, forests are cleared, new fields are made arable, the number of their inhabitants increases, lands are separated. On which new goods and farms are created-in short, the original Carolingian courtyards form the core of villages that have slowly sprung up around them and continue to grow. Soon these villages, which as "imperial land" are directly under the control of the emperor, proudly call themselves imperial villages and thus turn out the opposition to the "national inhabitants" villages, which have the respective prince of the country as their master.

Please observe the copyright of the city of Würselen.

For more information see here.

Some comments and explanations have been added.Such information is presented as follows:

Comments and explanations go here.